by James A. Bacon

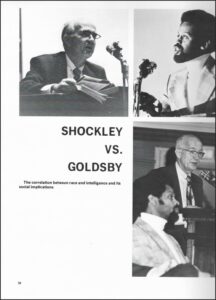

In August The Cavalier Daily ignited a furor over Bert Ellis, a conservative businessman whom Governor Glenn Youngkin appointed to the University of Virginia Board of Visitors. In a lengthy article, student newspaper detailed Ellis’ role, as a tri-committee chairman of the University Union, in bringing Nobel Prize winner William Shockley to the University for a debate about race and IQ.

Shockley’s views about Black intellectual inferiority have been broadly rejected by American society in the 47 years since Shockley went mano a mano with African-American biologist Richard Goldsby. But the event has been cited as the most damning of multiple reasons to demand Ellis’ resignation from the Board. As the UVa Student Council, the Democratic Party of Virginia and various media outlets have repeated the story, it has morphed into a narrative in which, to quote The Washington Post editorial board, Ellis “organized a campus talk” by a racist. No mention of a debate. No mention of Goldsby. No mention of the fact that Ellis was one of three student chairmen who ran the University Union.

Here’s what the narrative underplays or omits entirely: First, the University Union had reached out to local African-American groups in 1974 when planning the debate. Second, Ellis was one of three tri-chairmen who called the shots, although, as spokesman for the group, he was the only one quoted in The Cavalier Daily coverage of the controversy. Third, when the three tri-chairmen made the final decision, Ellis voted to cancel the debate. But he was in the minority, and he was overruled.

In sum, the portrayal of Ellis’ role in the controversy is so shorn of context that it amounts to character assassination. Here follows the full story.

William Shockley was widely acclaimed as the inventor of the transistor, an accomplishment for which he was awarded the 1956 Nobel Prize in physics. By the 1970s, he had turned his attention to the study of the inheritability of intelligence and its variability between the races. He propounded the view that Blacks had lower intelligence on average, not due to environmental conditions but due to their genetic inheritance. The idea, though held by many, was hotly contested. A series of debates had been organized, including one at Harvard University. The leaders of the University Union, the student-run group that organized major events, thought the topic would be of interest at UVa.

Harvard booked Roy Innes, a prominent African-American leader and director of the Congress of Racial Equality, to debate Shockley. The University Union wanted to replicate that format.

Before signing up Shockley and Innes, the University Union touched bases with two groups for feedback from UVa’s African-Americans. One was the Black Student Alliance, the other was the Minority Culture Committee. The idea was to schedule the event in February 1975 during Black Culture Week as a way to bring attention to that celebration.

Here is how, as quoted by the 1974 Cavalier Daily, Ellis remembered the interaction with Sheila Crider, Black Culture Week chairman: “She was asked as minority Culture Committee co-chairman to find out the black attitude towards the debate, and she reported that blacks would be in favor of them, book them.”

The Cavalier Daily also reported that Donald “Doc” Spell, Crider’s co-chairman, had agreed to the debate with the stipulation that someone other than Innes debate Shockley. He later came to oppose the debate in the face of “totally negative feedback” from Black students.

In an October 1974 letter to the CD, Crider denied that she had ever agreed to the debate. Yes, Ellis had reached out, but only to ask which date she preferred during Black Culture Week. “Ironic, isn’t it? To schedule a speaker on Black inferiority during a week dedicated to teaching Black achievement?”

Whatever the degree of buy-in from Black student groups early in the process, the mood shifted. Harvard students denounced the invitation to Shockley, and the debate there was canceled. For reasons unexplained in the Cavalier Daily coverage at the time — perhaps Spell’s insistence — Innes dropped out of the picture. As awareness of the upcoming event spread in the early fall of 1974, Black students at UVa began expressing vehement opposition.

The Cavalier Daily referred vaguely to “negotiations” between Ellis and Black student leaders but provided no details. Reading between the lines of the CD articles, Ellis was in a tight spot. As he said at the time, “Business-wise, you can’t sign contracts for a debate and three months later cancel. The agencies won’t stand for it.” He tried to find a solution that Black students could live with. One option mentioned more than once was to reschedule the debate so it did not coincide with Black Culture Week.

As the controversy unfolded, Ellis wavered. He asked the Student Council to give an advisory opinion. After what was described as a contentious, two-hour debate, Student Council voted 13 to 11 to advise the University Union to not hold the debate. Opponents declared Shockley’s views to be abhorrent and an insult to the Blacks attending UVa. Proponents generally took the tack that the UVa community should respect freedom of speech and be willing to hear unpopular viewpoints.

The Cavalier Daily quoted Ellis as saying that he would probably stand by the Council’s recommendation.

However, Ellis was not the final decision-maker. As the The Cavalier Daily reported:

The Union’s other Tri-Chairmen, Rick Kruger and Mary Dudley, said last night they will vote to retain the debate. This will offset Mr. Ellis’ vote and send the issue to the Union’s 22 co-chairmen, elected at large by the Union, for a decision.

As The Cavalier Daily had foretold, the University Union did, in fact, determine to hold the debate despite the Council’s recommendation. The Student Union co-chairmen voted by a decisive margin to forge ahead. However, the newspaper’s reporting provided seemingly contradictory descriptions of Ellis’ actions. First this:

Citing the Union’s efforts to go through proper channels in getting black opinion, the effects of a precedent cancelling a controversial debate, and the fact that such a debate would be an academic exercise, Union Tri-Chairman and Spokesman Bert Ellis urged the Co-[Chairmen] to not cancel the debate.

Then three paragraphs later:

Though Mr. Ellis did vote to cancel the debate, the Union’s other Tri-Chairman, Rick Kruger and Mary Dudley, voted to retain the debate. This sent the decision to the Union’s 22 co-chairmen, elected at large by the Union, for a decision.

Perhaps Ellis felt honor bound to live up to his promise to cast a vote in the University Union consistent with the Student Council’s recommendation, even if he did not personally agree with it. When asked about his stance back then, Ellis today tells Bacon’s Rebellion, “At one point I said, maybe we should just cancel it.” But seeing himself as a team player, he continued to speak, as spokesman, for the team.

Preparations for the debate proceeded, and the controversy faded from the pages of the Cavalier Daily. Wanting someone “formidable” to take on Shockley, the University Union recruited Goldsby, an African-American Amherst university professor and author of a 1971 book, “Race and Races.”

The debate was held in February 1975. The Cavalier Daily published a short front-page article that devoted several paragraphs to Shockley’s statements and only two to Goldsby’s.

In Ellis’ recollection Goldsby demolished Shockley, just as the debate organizers hoped he would. In his mind, the debate served to discredit Shockley’s racist premises. I reached out last week to Kruger, the behind-the-scenes champion of the event to see if he shared Ellis’ view, but he declined to respond to my email. In reviewing the CD archives, I could find no letters to the editor commenting on the debate one way or the other. One thing can be said for certain: The controversy over Shockley died and remained buried for 47 years until the Cavalier Daily resurrected it this August.

The severe lack of critical thinking skills in this current “campus generation” smacks of intellectual laziness and appears as a mental shortcut to reinforce their mantra of “We know better than Boomers because we think we do.”

I was a Student Council Representative from the College during that “contentious, two-hour debate,” and it was my vote that swung the result to 13-11. We’d had an earlier vote that was tied, I think. I switched my vote from advising the UU to hold the debate to opposing. The reason was that the two motions were different. The second motion was a simple statement of advice. As various people have recalled, by that time, notwithstanding the strong arguments on both sides, the whole invitation had become so fraught and divisive that some of us, as representatives of all the students, thought it best, if the UU wanted our opinion, to just say no debate. But it was very close, not only in the Council but also in our own minds. We were for free speech, and we were certainly used to hearing contentious debates and controversial speakers, but this case had become heavily burdened, and it looked as if the black students—and remember this was a nascent community—really were opposed. To go ahead in the name of free and open debate was fine, except it was starting to look like a major thumb in the eye of our fellow students. Also, remember, this was not Council’s regular business. We didn’t resent being asked, but we did the best we could and finally gave a simple “no” without additional rhetoric or argumentation. Often in later years I thought maybe I should have voted to have the debate. I had close friends on both sides. Under considerable pressure, we did the best we could. It was not a simple matter. The lesson today for the CD and other moralizing crusaders is to have some understanding of the context and the difficulties people faced back then. One hesitates to use this language, but, yes, there were good, conscientious people on both sides of that discussion.

Thank you for providing critical context to the controversy.

Wow. From a person actually there. Thank you.

Could any student currently on Student Council offer such a complete statement? Or just broad, overly-simplistic, virtue signaling categorizations?

I think your recitation of the times and the tenor of the debate and the many different elements you were trying, in good faith, to deal with reflect very well on all involved in hindsight…

You acted like young adults and did the best you could…

Thanks very much. Yes, the average age of the undergraduate representatives was only about 20, and, even though the debate lasted two hours (on a Tuesday night after classes and everything else), after motions and arguments, we had only about a minute to decide. We couldn’t take the next five years to read and contemplate Burke on prudence—and even then the decision would have been difficult.

As you know, this era, circa 1975, was before cancel culture, and we were not disposed to de-platforming anyone. In fact, we undergraduates had come in just one to two years after huge debates (upheavals) at the University over the national issue of the Vietnam War and the local debate over university enrollment growth. None of us attended lectures and debates to have our views confirmed; the whole experience was an intellectual free-for-all, if not always a feast. It was a time of both hippie students and a few remnant traditionalist males in coat and tie. No decision we could have made could have come without a downside; advising against having the debate was not a slam-dunk move.

As I recall, another problem was that, although Shockley was a Nobel Prize winner, his expertise was physics and the transistor, not any natural or social science that dealt with the study of race. So there was also this feeling of, Why would we want to invite this person in particular?

So without making any long-winded, moralistic statements, we simply said, hey, if it were up to us, we wouldn’t be inviting Shockley to campus. And, as you also saw, we gave our opinion, but apparently it didn’t matter that much to the Union in the end anyhow. Then, as the narrative says, students moved on. As I recall, it wasn’t an issue—unlike some concerns about the honor system or the football coach—that roiled the Grounds for months on end. And Student Council in particular I don’t think received much flak one way or the other. A few of my fellow representatives were annoyed with me for changing my vote, but I explained my decision, and their perturbation passed pretty quickly.

Also, we took ourselves pretty seriously, but we didn’t take ourselves all that seriously. We knew we were not—and were not capable of—making apodictic judgments good for eternity. We did have some awareness of our relative youth and inexperience. So, yes, we knew that doing our best was all we could do. But you couldn’t be absolutely certain you were right.

Btw, there had been divisions over the Vietnam War, but otherwise there was little sense of political party. There were R and D clubs. I was in YAF and Young Republicans. But we all had the sense that we were still learning, after all. So our friends and roommates were all over the map. Because we did have some self-awareness and therefore humility, we didn’t take our views with ultimate seriousness. We recognized that we were all still very much in via.

The kids today have no idea what they are missing. I was 4 years after this, and we had free speech AND all got along!

Btw, I’ve been mulling this over. I think it’s fair to say that we (on Student Council) had two other thoughts in mind as well:

One was that we as representatives were not just voicing our own opinions, although our debates could sound like that. We did have some awareness of our responsibility to try to do what seemed best for the University as a whole at that moment. That view might be in tension with our personal views, but we had to try to see matters in this larger perspective.

I also seem to recall our sense that the debate invitation was not a simple free-speech issue. Anyone could come to the Grounds and speak. (And occasionally some odd interlopers did pass through, staying in local houses for a time.) The question was did we recommend that the University Union invite and pay for both these men to appear? So some of us did respond, first inside our own heads and with a kind of seat-of-the-pants assessment requiring further analysis, No, I don’t want to pay Shockley to come here.

Sounds like the Cavalier Daily is a mini NY Times – they only print the news that fits

A couple of date errors: “As awareness of the upcoming event spread in the early fall of 2024, Black students at UVa began expressing vehement opposition.” “The debate was held in February 2015.”

Thank you for spotting those careless typos. That’s what can happen when you don’t have anyone proof reading behind you. Dates fixed.

Incredible!

Jim, superb article providing the full historical context. It is a pity that the Cavalier Daily refuses to provide true, historical context, preferring to paint Bert as a racist when the exact opposite is true.

What has happened to truth and honor on the Grounds?

The Cavalier Daily appears to have no interest in “true, historical context”, nor in a comprehensive, extensive presentation of our history and those people who whose actions and ideas shaped it.

It is apparent that the truthfulness of the Shockley debate is of no interest to those who are intent on the destruction of the truth of this nation’s founding. Beyond that, the destruction of the moral and ethical tenets that make up our increasingly tenuous social, moral and political cohesiveness, are necessary preconditions to achieving their goal,

Perhaps the CD needs to be reminded that “It is always better to have no ideas than false ones; to believe nothing, than to believe what is wrong.” -T. Jefferson

Another interesting aspect of the Student Council debate was that we were acutely aware of what we were not aware of: knowledge of Shockley and his positions. No Internet databases, no articles of his that we read, no peers at Harvard or wherever who knew something about him. That ignorance feels kind of embarrassing now. All we’d heard were a couple of phrases about him. So historically it’s important not to view that debate through the lens of current knowledge. If we’d known he was a racist crank, we would have been wiser in our deliberations and probably less abstract.

We did know enough to be decidedly uneasy. The job of the University Union was basically that of what other universities call a Student Activities Board: bringing in programs to please or instruct students, or both. It didn’t feel as if the Shockley debate would be either entertaining or educational. His fee would come out of the mandatory Student Activities Fee, and our only major constituent group that expressed a strong view was now opposed.

So, frankly, we were not as well informed as, even in that era, we probably could and should have been, but we knew enough to be apprehensive and wary, notwithstanding our general view in favor of the winnowing process of vigorous debate.

The dog that didn’t bark in this story?

it appears that “free speech” won. Not in the abstract concept of free speech as a social good, but in the concrete results of allowing the speech.

What TJC has been saying, and what Jefferson believed. Would be nice if the BOV and the Admin gave more than lip service to it…

Well, yes, we can imagine the chance to schedule a debate between, let’s say, Lord Haw-Haw and Anthology Eden in 1940. That would be great; we’d love to see the latter wipe the floor with Haw-Haw. Or a debate between a leading Communist and W. F. Buckley Jr. It probably happened. That would be terrific. Very exciting. The sponsors could in no way be put down as Nazi sympathizers or Communists.

But what if a university group asked about the propriety or at least the desirability of inviting a notorious anti-Semite to campus to debate? And the leading Jewish groups complained vehemently. And Student Council was asked for advice by the sponsoring group. I assume Council would be within reason and their rights to ask, Can’t you do any better than this??

Here’s what the situation was really like: African-American students and women were still relatively new to the University (the College, Engineering, etc.) At the time of the debate we’re talking about, ALL the Student Council presidents and Honor Committee chairmen had been white males. Which was fine except now we were trying to welcome other groups into the University. Blacks and women were regularly elected to Student Council—not out of white guilt but just a widespread desire to open opportunities to all and welcome them into the mainstream of University life.

So an analogy might be: Imagine a family of Romani who have moved into your neighborhood. Two months later a debate is scheduled for the local community center on the topic “Gypsies are a lying, thieving people.” And the opponent has data and evidence to establish that by and large the Roma are not as represented.

A bare-steel principle of free speech and debate could be invoked, but would this scheduled event strike anyone as welcoming and neighborly?

A simplistic example, but it conveys other factors at work in our thinking and ethical concerns. As my dissertation supervisor Kenneth W. Thompson used to say, The difficulty is not choosing between right and wrong but, more often, making our way in a maze of competing principles.

And I think the answer to the competing principles is to err on the side of free speech. The problem with your examples of gypsies is who decides whose ox is gored? Quis custodiet custodes? Our present speech is being censored. The government is acting through private companies. UVA Law is silent. Social media has kids self-censoring. Why does Google or Fakebook get to decide what is allowable speech? And they have been often wrong! They censor Alex Berensen and Chris Rufo and then have to admit months later they were actually right.

One of the few things Jim Ryan has said that I agree with is “The answer to speech that offends is more speech.” Of course, he only meant that in defending Hira Azher, not in people who disagree with him…

Yes, I understand. Here’s a good counter example to my case of the antisemitic speaker. It’s even more extreme.

A group wants to sponsor a debate between a well-known Holocaust denier and a University historian or Religious Studies professor who’s an expert on Jewish or WW2 history. The local Hillel says, Great! Bring it on!

The only problem with that scenario is that I’d wonder if you could find a single person among the 50,000 students, faculty, staff, and medical center personnel who denies the Shoah. But apart from that, it would be great to hear a great local authority put paid to the denier’s arguments once and for all.

What I’ve tried to indicate above has been the context of the situation when Student Council debated and decided. Apparently some people are interested in those events after they’ve lain dormant for all these years.

As an ethicist, I’d note that moral decision-making doesn’t involve applying one rule or principle in a vacuum but rather calling upon all the resources of phronesis, practical judgment, to apply moral principles within a confusing welter of facts and speculation, competing norms, and community standards to bring about the best result, apart from one’s own desires and interests, and all taking place under pressure of time and circumstance and within the University student’s commitment to honor and duty.