by James A. Bacon

University of Virginia old-timers (like myself) remember what it was like to find help in picking courses and deciding majors. We’d latch ourselves onto a professor who took an interest in us, and he or she would walk us through the process. It did require some initiative on our part to reach out, but then, we were accustomed to taking matters into our own hands. I was fortunate. My advisor, history professor Joseph C. Miller, was not only a charismatic teacher and a leading scholar in his field, but he regarded the care and tending of students — even lowly undergraduates like me — as part of his vocation.

That’s not the way it works anymore. Faculty members are still expected to play a role in advising students, but it is a much diminished one. At UVa, responsibility for dispensing advice has been bureaucratized.

At the UVa Board of Visitors meeting Wednesday, the Ryan administration highlighted what it is doing to improve student advising. The dominant themes of the session were (1) the student experience is lacking for many, and (2) the answer is hiring more advisors and investing in the latest, greatest technology.

The picture that emerged is that UVa has numerous fragmented initiatives at the school and college level but no coherent university-wide vision. Practices vary widely. The cost of programs was not discussed. No cost-benefit analysis has been conducted. With no clear objectives beyond “we want to be the best,” there are no logical limits to an endless expansion of programs.

It was evident from the presentations that some very earnest, well-meaning people have been working on the issue for a considerable time, but the Board heard no analysis of how the perceived problem came to be, nor did anyone suggest that the answer might be returning responsibility for advising students to the professors. Blasted with a firehose of information, Board members were given little time to formulate questions.

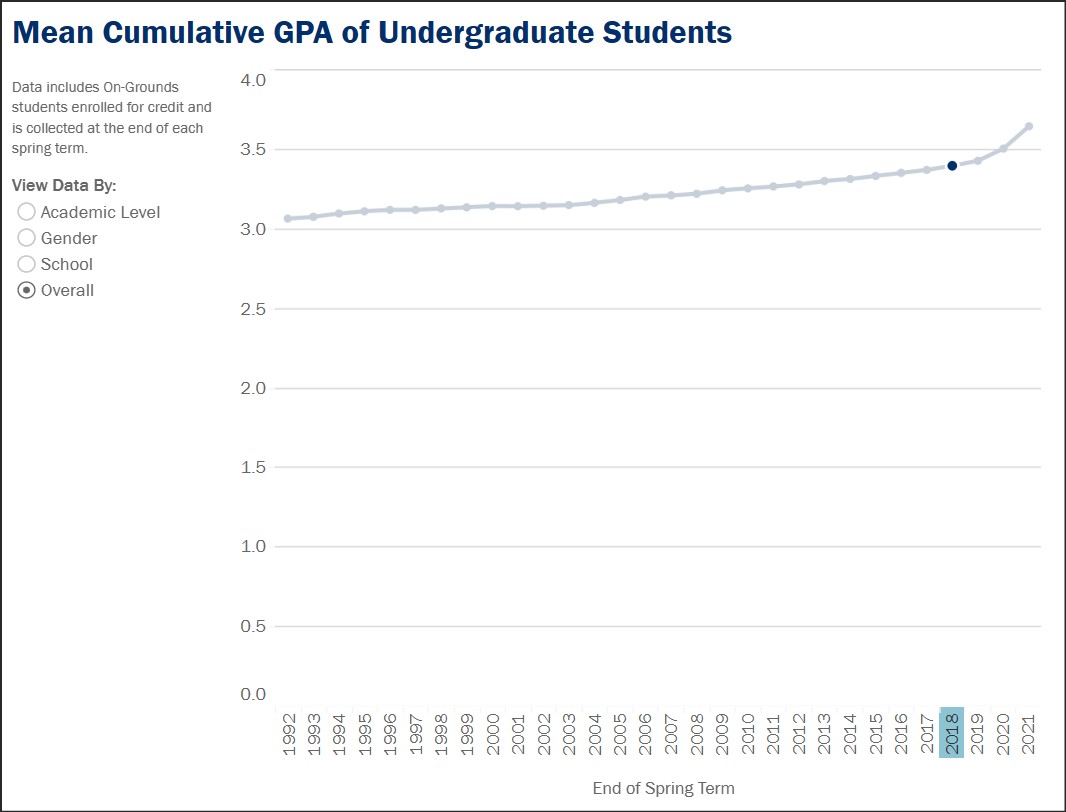

One obvious question, never posed, is how much it costs to advise students. The inflation-adjusted cost of “student services,” of which student advising is a significant component, increased 22.4% between 2012 and 2022. To what degree does expansion of advising programs contribute to the ever-rising cost of running the university — costs that must in turn be covered by higher tuition? Continue reading

by Loren Lomasky

by Loren Lomasky