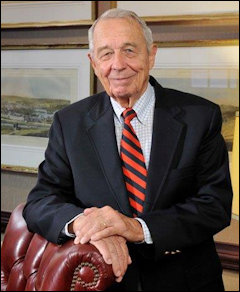

Editor’s note: E. Morgan Massey graduated from the University of Virginia in 1949. A member of the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity, he was a generous donor to the School of Engineering and the Darden School.

by James A. Bacon

Virginia lost one of her greatest sons today when E. Morgan Massey passed away after a brief battle with cancer. As author of his authorized biography, I had the good fortune to get to know him these past three years. At 94 years, he was a kind man, and a gentle man, and the people who knew him loved him.

One of the U.S. coal industry’s great innovators, he presided over the transition of the family-owned A.T. Massey Coal Co. into a subsidiary of the publicly owned St. Joe Minerals, and then through a series of mergers and acquisitions into a partnership between Royal Dutch Shell and the Fluor Corp. Under his leadership, A.T. Massey Coal became the third-largest coal company in the U.S. Then, when forced to retire at 65, he struck out on his own in competition with the world’s biggest energy giants to build new coal-mining enterprises in Venezuela and China. The Venezuela gambit was only modestly successful but the Daning mining project was a home run. He surely was one of the oldest start-up entrepreneurs in the history of American business. Before he died, he was coming into the office every day to work on his latest venture, Minerals Refining Company, which utilized Virginia Tech-developed technology to capture microscopic coal fines.

But Morgan was more than a successful businessman. He was a prophet, and that is how I hope people will remember him. Nearly 30 years before the Business Roundtable issued its famous “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation,” articulating corporations’ obligations to stakeholders, Morgan had written “The Massey Coal Company Doctrine,” which served as a business and ethical guide for A.T. Massey Coal. It was the intellectual achievement of which he was most proud, and rightfully so.

As Morgan saw it, A.T. Massey had four overriding objectives: (1) supply customers with coal of the best quality at a reasonable and competitive price; (2) provide acceptable rates of return on capital; (3) provide the best possible well-being for employees; and (4) be a good corporate citizen. Here’s how I summed up his thinking in my biography, “Maverick Miner”:

The customer sat at the apex of Massey Coal priorities, not because the customer was intrinsically more worthy but because without customers, there is no business enterprise and the other objectives are unachievable. “In our free enterprise economic system,” Morgan wrote, “the customer is the primary reason for a business to exist.”

Morgan argued that stockholders came next in the hierarchy for a simple reason: Without capital, no business can sustain itself. At the time he was writing in 1982, Massey Coal was a joint venture partnership between two corporate owners — Royal Dutch Shell and the Fluor Corporation (which had just acquired St. Joe Minerals). Although it was in Morgan’s personal interest as a Fluor stockholder to maximize Massey Coal profits, he did not express a goal of profit maximization. Instead, he argued, shareholders deserve an “acceptable rate of return.”

The third corporate objective was providing the “best possible well being” for employees, also without whom no business can function. Morgan defined well being as consisting of the following: better-than-average wages and salaries; a safe and healthy work environment, superior sickness and health benefits, attractive retirement and capital-accumulation plans, and a sense of belonging in an organization where employee contributions were valued and recognized.

The fourth objective was community well being. At the time Morgan was writing, the coal industry was not known for its commitment to the effective governance of the states, counties and towns where their employees lived. Long before, when the amenities offered by coal camps were needed to recruit labor, companies invested heavily in roads, housing, water, electricity, schools, churches and even opera houses. But the rise of personal mobility that came with automobiles and roads allowed miners to live anywhere, and most companies divested themselves of housing, stores, utilities and ventures peripheral to the business of mining coal. Morgan had no interest in providing these amenities, which fell outside his field of expertise and could be delivered more effectively by others. Rather, he insisted that Massey Coal make a positive contribution to the communities of which it was a part by being a “responsible citizen.”

Morgan was a generous philanthropist, but not because he sought recognition. Indeed, when the Virginia Institute of Marine Science offered to name a new Innovation Fund after his wife Joan and him, he turned down the honorific.

Morgan was a man of principle. The mission statement he wrote for the Joan and Morgan Massey Foundation sums up his view of how to build a better world.

During our lifetime, we have seen our government focus to an ever-increasing extent on the support of that segment of society least able to support itself. We believe that this destroys one’s incentive to succeed, leading to greater dependence on government to provide basic necessities and, in the long run, to more poverty. Because of the relatively short-term horizon of our democratic political selection, the priority of reelection has put the emphasis on social programs at the expense of long-term programs like education. Compounding this problem, government had mortgaged the future of succeeding generations by increasing taxation on the creation of wealth and surtaxing higher income levels to support its social programs. Creating greater wealth and thereby greater income to be taxed is the only way to finance a future overall prosperity for our country.

I thought Morgan would last forever… well, not forever, but longer. He was physically vigorous for a 94-year-old man. He took regular strolls around the Fan neighborhood in Richmond where he lived, and he still drove his own car to work every day. His mind was still sharp, though perhaps not as acute as it once had been. His name recall would fail him periodically when speaking of events, oh, 50 or 60 years ago, but his memory overall was astonishing. I am deeply saddened by his death because I will miss him, but I will not mourn him. He lived a long life, a full life, and a rewarding life right up to the end. The end came quickly. I can think of no better way for anyone to make their departure to that great coal mine in the sky.